Last week, Zach Lowe was on a podcast discussing his All-Star selections and mentioned that he has a spreadsheet with a bunch of different advanced stats — PER, RPM, VORP, etc… — to help him compare players. It also sounds like he is adding these advanced stats together to create some sort of Frankenstein advanced stat. Listen in (starts around the 58:00 minute mark) or read my rough transcription below.

By the way. Why have we not talked about Christian Wood. So on my advanced stats little spreadsheet here—number one when you add up all the categories and then you add up all the other categories and take away that, whatever it is, number one is Christian Wood.

While it is true that it’s better to have a higher value than a lower value for pretty much any stat, it’s a bad idea to add different stats together and draw conclusions from the combined value. That’s because the range of potential values can vary dramatically depending on the stat being used.

For example, Nikola Jokic leads the league in PER (Player Efficiency Rating) at 31.3, which is about six points higher than the 10th place player in PER. Jokic also leads the league in VORP (Value Over Replacement Player) at 3.3, which is only a point and a half higher than the 10th place player in VORP. In other words, there’s more spread in PER than there is in VORP. And if we were to add them together it would erase the fact that a single VORP point is “worth” more than a single PER point. In other words, at this point in the season, a player with a PER of 30 and VORP of 5 is more impressive than a player with a PER of 33 and a VORP of 3, but you wouldn't know that if you just added those two values together.

Let me put it another way. Imagine you’re a college admissions officer and you’re asked to admit one of two students based solely on their SAT and ACT scores (for non-Americans, the SAT and ACT are standardized tests that some, but not all, high schoolers have to take to gain entry into college/university).

Student A scores a 1400 out of 1600 on the SAT and a 25 out of 36 on the ACT.

Student B scores a 1300 out of 1600 on the SAT and a 35 out of 36 on the ACT.

If you were to combine each student’s test scores into one number it would appear that Student A is the superior applicant with a combined score of 1425 compared to Student B’s 1335. But admissions officers are admitting Student B over Student A ten times out of ten. That’s because ten additional points on the ACT are a lot harder to come by than 100 additional points on the SAT. We lose sight of that when we add these values together. Same goes for adding things like PER and VORP together, albeit on a smaller scale.

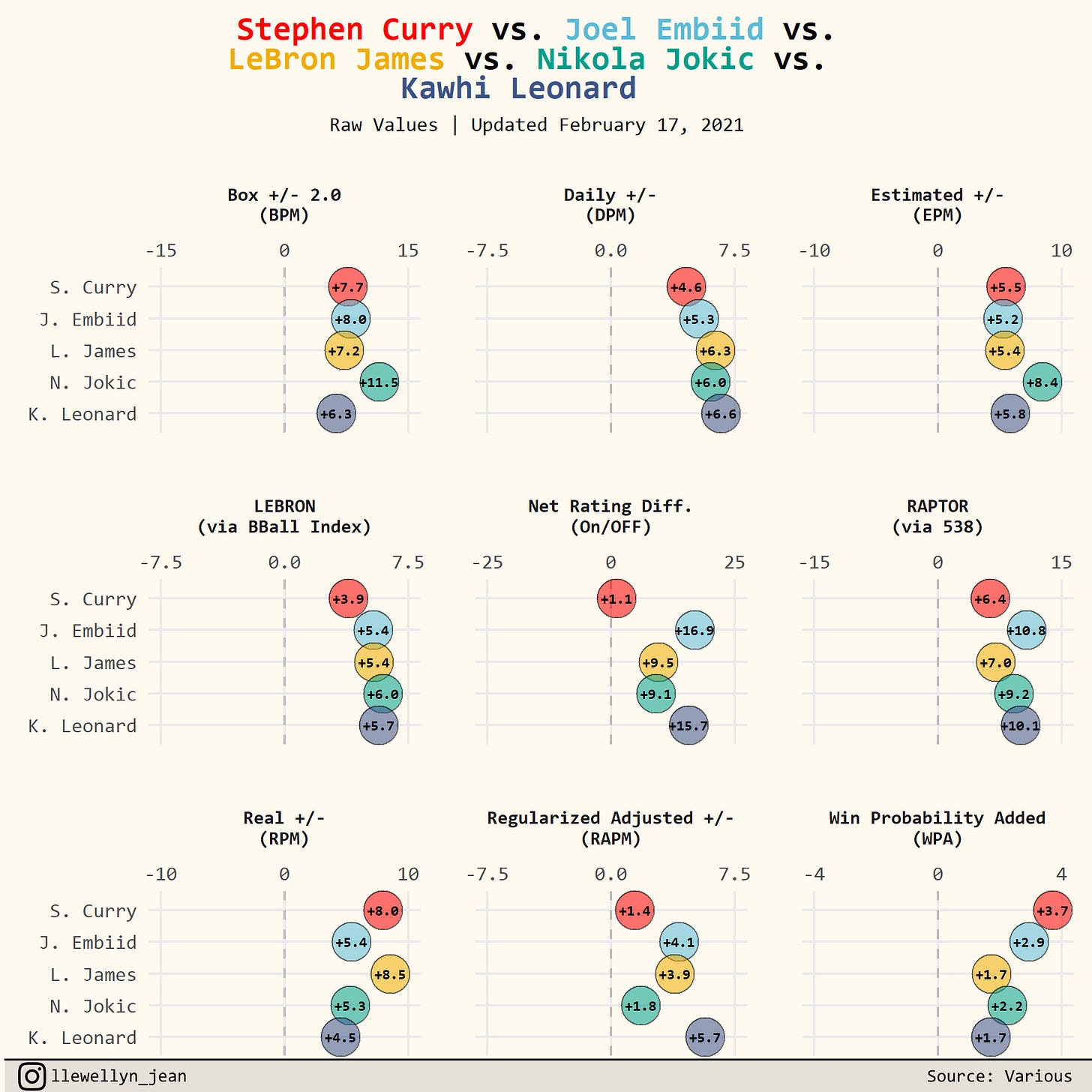

Anyway, that podcast segment inspired me to create my own little advanced stats spreadsheet. It includes the following advanced/impact metrics:

Box Plus/Minus 2.0 (BPM) by Daniel Meyers

Daily Plus/Minus (DPM) by Kostya Medvedovsky

Estimated Plus/Minus (EPM) by Taylor Snarr

Luck-adjusted player Estimate using a Box prior Regularized ON-off (LEBRON) by Krishna Narsu and Tim/Cranjis McBasketball

Net Rating Differential (On/Off) from basketball-reference.com

Regularized Adjusted Plus/Minus (RAPM) by Ryan Davis

Robust Algorithm (using) Player Tracking (and) On/Off Ratings (RAPTOR) from fivethirtyeight.com

Real Plus/Minus (RPM) from espn.com

All of these metrics are publicly available and what each attempt to do in one way or another is quantify how much a player worth to their team, typically on a per 100 possession basis. These stats are far from the only way to evaluate a player, but they’re nice to have—especially when they’re all in one place. Here’s a sample based on ten players I picked out of a hat, sorted alphabetically (click/tap to enlarge).

We can also do fun things (fun for me, anyway) like put the values into a small multiples chart to make it easier to see who these stats like the most (spoiler: I don’t think there’s an overwhelming favorite).

Zach Lowe, if you’re reading this and want access to my spreadsheet, send me an email.

Atypical All-Stars

Now that everyone freely admits that the NBA All-Star game is about money and nothing else, lets talk about how we can make it more profitable.

Instead of selecting All-Stars based on some combination of media, fan, and coach-input, I’ve come up with my own approach, which I think will maximize the number of people who will tune in to watch the game.

By combining PER from Basketball-Reference and daily pageviews from Wikipedia I created a metric to determine starters, reserves, and wildcards from each conference.

PER, while obsolete, is pretty good at identifying who casuals think are the league’s best players—which in addition to kids, is who the All-Star game is for anyway. Meanwhile, pageviews on Wikipedia can give us a sense of who are the league’s most intriguing players. LeBron James, Stephen Curry, and James Harden rank first, second, and third in pageviews this season. Also, to add a pinch of recency bias, I limited my analysis to the median number of pageviews on Wikipedia over the last 30 days. Lastly, I multiplied PER and pageviews by each other to create what I’m calling the Atypical All-Star Score™.

Let’s start in the East.

The NBA requires each team to have four backcourt players (two of which are starters), six frontcourt players (three of which are starters), and two additional wildcard players that can be from either position group. That’s a total of 12 players.

By my Atypical All-Star Score™, the starters in the East would be Kyrie Irving, James Harden, Kevin Durant, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Joel Embiid. All five players are immensely popular and are having stat-stuffing individual seasons. No controversies here.

The reserves are where things get spicy. We have LaMelo Ball, Derrick Rose, Jimmy Butler, Tacko Fall, and Jayson Tatum. The wildcards, which can be from either position group, would go to Bradley Beal and Russell Westbrook.

The case for why LaMelo and Rose should be in the All-Star game is simple. They’re popular as all get-out. The only players with more Wikipedia pageviews over the last 30 days than both LaMelo and Rose is LeBron James, Stephen Curry, Kevin Durant, and Kyrie Irving. For Rose, some of that is driven by the fact that he was recently traded to a team with one of the largest fanbases, but he’s been one of the most popular players in the league for years, especially overseas. Meanwhile, LaMelo is must-watch TV every time Charlotte plays. If our goal is to generate buzz (go Hornets), then he has to be on the team.

By the same token, the All-Star game would be better with Tacko Fall in it. Who wouldn’t watch every single second that he’s on the court? Every player on the other team would be loading up to try and dunk on him and he’d be looking to do the same to them. It’d be the perfect respite for those stretches of the second and fourth quarter of the All-Star game when the starters are on the bench and everyone watching is half asleep anyway.

As for Russell Westbrook, he gets to be on a team with Durant and Harden one more time. Fun for him and for his fans.

In the West, the starting five goes chalk with LeBron James, Stephen Curry, Nikola Jokic, Kawhi Leonard, and Anthony Davis leading the way.

Luka Doncic, Damian Lillard, Zion Williamson, Carmelo Anthony, and Karl-Anthony Towns round out the reserves, with Chris Paul and Lonzo Ball sneaking in as wildcards.

Let’s swap out Karl-Anthony Towns, who has missed too many games this season, for the next highest scoring frontcourt player according to my Atypical All-Star Score™, which is Rudy Gobert.

The Carmelo Anthony selection follows the Derrick Rose rule. Now both conferences will have an older player on their roster who was once good, but is still popular among players and fans.

Many will say that someone like Lonzo doesn’t deserve to make the All-Star game over someone like Mike Conley, but deserve’s got nothing to do with it. We’re trying to make money. And the fact is everyone outside of Salt Lake City and Memphis would rather watch Lonzo guard LaMelo than watch Conley run pick-and-rolls and not turn the ball over for 15 minutes.

To be clear, this is a dumb exercise and not meant to be taken seriously. But if no one really cares about the game anyway (they don’t) and the goal is to make money (it is) then I think the NBA is leaving stacks of cash on the table. With my method, we still get to see the best players at the start and end of the game, but the boring in-between parts become substantially more intriguing.

Cool But Useless

Recently, I saw one of those population maps drawn in the style of the Unknown Pleasures album cover. These type of plots are immensely popular because they look cool as hell. Kirk Goldsberry created one earlier this year based on the distribution of shot attempts by distance from the hoop for a select group of NBA players that I thought turned out nicely.

So I took a stab at creating my own based on the location of every shot attempt this season, mapped onto the dimensions of an NBA court.

Premium subscribers to The F5 receive a tutorial on how to create the graphics in this newsletter every Friday.

Great writing Owen. Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

Benbo

Twitter: https://twitter.com/benbobets

Substack: https://benbo.substack.com/

Great article. LOVED the shot chart. Any chance you make the spreadsheet available?