Rather Be Healthy Than Good

On the role of health and luck this NBA season

The Utah Jazz are having a moment. They’re 20-5 with the league’s best Net Rating. No one has buyer’s remorse on the Rudy Gobert contract extension. Everyone is suddenly a Jordan Clarkson fan. And Mike Conley could finally make his first All-Star game.

It must also be mentioned that up until recently Utah’s core has been unusually healthy.

Aside from the two games that Donovan Mitchell missed last month due to a concussion, and Mike Conley’s recent hamstring flare-up, Utah has been the picture of health. So far, the Jazz have used only three different starting lineups all season. Only the Sacramento Kings, who are on a hot streak of their own, have used fewer.

The chart above shows the cumulative number of different starting lineups each team has rolled out over the course of the season. Teams are ordered by their total number of starting lineups used as a percentage of games played.

The Miami Heat sit atop the chart, having used 16 different starting lineups in their first 24 games. The Heat have had to rejigger their starting lineup every other game due to COVID health protocols and other general nicks and scratches. According to data from Spotrac.com, nine players on the Heat have missed a combined 30 games due to health and safety protocols. Only the Dallas Mavericks have more games missed for the same reasons.

Compare Miami and Sacramento in the chart below, which visualizes the number of distinct starting lineups each team has used. Both Miami and Sacramento have played the same number of games, but one team has had to use eight times as many different starting lineups as the other. Is it really shocking then that the Kings are a .500 team while Miami has stumbled out of the blocks? Or compare the suddenly spunky San Antonio Spurs, who have only used five different starting lineups, to the Dallas Mavericks, who have used 12 different starting lineups—and none for longer than five games. Is it starting to make sense why the Spurs are the sixth seed in the Western Conference while the Mavericks are in the lottery?

It’s tempting to say that good teams are healthy teams, but if we want to be specific it’s more accurate to say that most of the early season surprises come down to health. Many of the teams that are playing surprisingly well this season have had a high amount of continuity in their starting lineups. At the same time, the teams that are playing surprisingly poorly are basically using a random lineup generator.

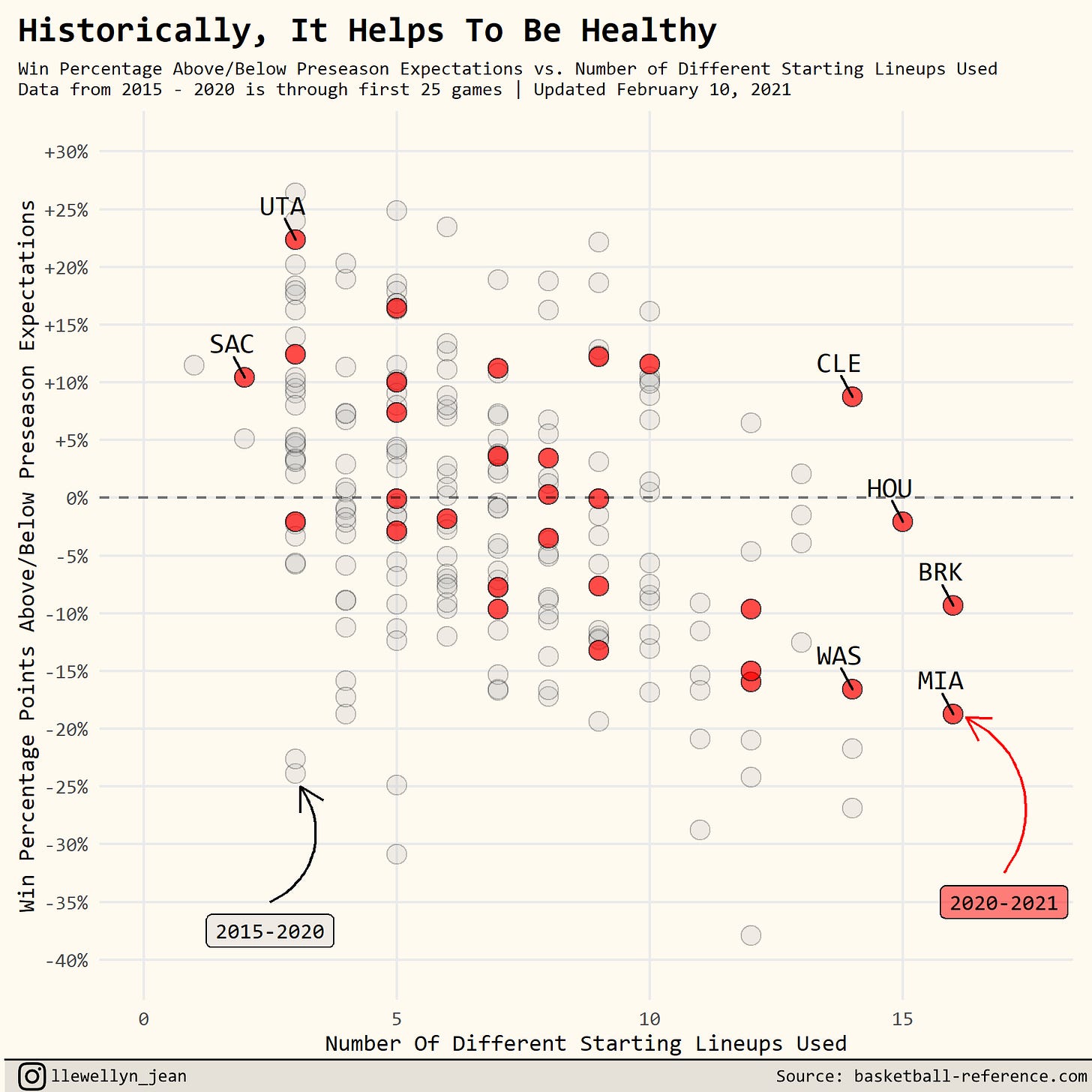

One way to think about this idea is to look at the relationship between how well a team is playing relative to their expectations coming into the season and how much continuity they’ve had in their starting lineup. The chart below shows each team’s current win-percentage above or below their projected win-percentage from the preseason (based on their over/under win total) versus the number of different starting lineups they’ve used, adjusted for games played.

Any team above zero on the horizontal axis is winning more games than would have been expected coming into the season, while teams below the dotted line are winning fewer games than expected. Although the relationship is not a perfect one-to-one, you can draw a linear trendline running from the top left of the chart to the bottom right. Meaning, on average, the fewer starting lineups a team has had to use this season, the better off they have been relative to preseason expectations. Conversely, the more starting lineups a team has gone through, the worse off they’ve been. To put it simply, surprisingly good teams are surprisingly healthy.

I should mention that the causality could run both ways — a team playing surprisingly poorly might be more inclined to shake things up and use different starting lineups — but based on what we know about why so many teams are going through different starting lineups (COVID), it seems more likely that roster discontinuity is adversely impacting team performance rather than the other way around.

Looking at the continuity in the starting lineup is not the only way to get a picture of a team’s health. After all, an injury to a key bench player can be just as impactful as an injury to a starter. Additionally, not all starters are equal. Losing Karl-Anthony Towns is going to have a bigger impact on a team than losing Juan Hernangómez. In other words, if anything, the previous chart makes teams like the Hawks (who have missed games from key bench contributors) and the Timberwolves (who have missed games from their best player) look healthier than they really are.

Because of this, I also looked at the relationship between a team’s win-percentage relative to preseason expectations versus the average amount of cash the corresponding team has spent on injured players per game. Salary, while not a perfect representation of player value, is a little better than just using starter designation to measure a player’s worth to a team.

Although the relationship isn’t as strong (or as linear) as in the previous chart, I think it tells a similar story overall. Once again, we see a cluster of teams in the top left corner of the chart and in the bottom right corner. Broadly, this indicates that overperforming teams have been healthier on average than teams that are underperforming.

(Note that some of the cash being spent on injured players is already baked into a team’s preseason expectations. For example, The Warriors are paying Klay Thompson around $400,000 every game he misses with his Achilles injury. But that was known before the season and the Warriors’ preseason expectations account for that. To make sure I’m only capturing cash spent on players whose injuries would effect over- or under-performance, I omitted cash spent on the following players: Klay Thompson (GSW), Jaren Jackson Jr. (MEM), Justice Winslow (MEM), Al-Farouq Aminu (ORL), Jonathan Isaac (ORL), and Kris Dunn (ATL))

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that one of the biggest positive outliers on both of the previous charts is led by a frontrunner for MVP and an early season Coach of The Year candidate. The Philadelphia 76ers have exceeded expectations far more than we’d expect for a team that’s dealt with as much roster discontinuity as they have and Joel Embiid and Doc Rivers will both deservedly get a lot credit for that.

If all these charts seem like a lot of work to show something so obvious, then you’re probably right. But I don’t think health and general luck is mentioned as often as it ought to be when discussing why a team is suddenly succeeding (shoutout to John Hollinger for being the only analyst I’ve seen mention it with respect to the Jazz).

Meanwhile, the lack of health is often the first thing that’s mentioned as an excuse for why a team is playing poorly. This isn’t surprising. It’s the natural way that humans tend to represent reality. When times are tough, we blame our problems on bad luck or things that are outside of our control. And in the good times we point to specific actions or changes that we believe brought about our good fortune. It’s more exciting to say that Jazz are playing well because Donovan Mitchell is a stealth MVP candidate than it is to say the Jazz are playing well because they’ve benefited from injury-luck.

But health and luck is an especially relevant factor this season in which COVID casts a long shadow over everything. The chart below shows each team’s win percentage relative to preseason expectations versus the number of starting lineups used. This time I also included data going back to 2015 as a reference.

Between 2015 and 2020, no team used 15 or more different starting lineups through their first 25 games. Already this season, there are three teams that meet that criteria. Surely, teams like Miami and Brooklyn will find some continuity as players come back from injuries and integrate into the starting lineup. Still, it’s worth emphasizing just how lucky teams like Utah, Sacramento, and others have been to not have to deal with this issue.

I’m not suggesting the Jazz are frauds or that the Heat don’t have anything to worry about now that they’re healthy. I just think we need to be more open and honest about the outsized impact of external forces that shape whether a team succeeds or fails. It may not be exciting, but it’s real.

State Of The MVP Race

Two weeks ago LeBron James took over the top spot in The F5’s MVP Model and has pretty much been there ever since. If the Lakers continue to steam roll everything in their path and James doesn’t take too many games off, then I think his case for the award will be tough to beat.

You wouldn’t know it if you only followed the national media, but Giannis Antetokounmpo is having another MVP-caliber season. His odds of winning the award are third best in The F5’s MVP Model, but sixth best in betting markets. So if you’re looking for some value then throwing a few bucks at the top Buck isn’t the worst idea.

Speaking of Antetokounmpo: I understand why the media isn’t talking about him as an MVP candidate, but I’m surprised there isn’t a groundswell for his campaign among fans after he signed the super max contract. I would have thought given all the hoopla leading up to his decision fans of competitive balance and small market teams would be celebrating Antetokounmpo more.

Also, keep an eye on Donovan Mitchell’s MVP odds. The Utah Jazz are too good to not have someone in the conversation for the award and even though I’m not sure he’s the team’s best player, he’s definitely the face of it.

I Didn’t Know I Couldn’t Do That

So it turns out you can’t actually just give money away to people. Over the weekend, I received a stern email from Stripe — the payment platform used to process Substack subscriptions — indicating that they were kicking me off the platform for violating section A.7.b of the company’s Service Agreement, which prohibits accepting payments for gambling and games of chance.

After some back and forth with Stripe’s support team I got my account back under the condition that I stop giving away free money to random subscribers. This means The F5 will no longer have monthly lotteries or giveaways. If you signed up for a premium Substack subscription to The F5 and now want your money back because your expected value just went to zero, send me an email.

Hey if we need a re-send of this code for the small multiples because we just joined how do we request without bugging you